The Prisoners of the First World War

During the early years of the war, Germany captured many more prisoners than Britain (see here for an account of a group of Scots Guards being surrounded and taken prisoner). By 1915, there were estimated to be over 1 million prisoners of war in Germany, far more than the authorities had anticipated. These men often had to sleep in fields, suffering from exposure while camps were built to house them. Often they built the camps themselves.

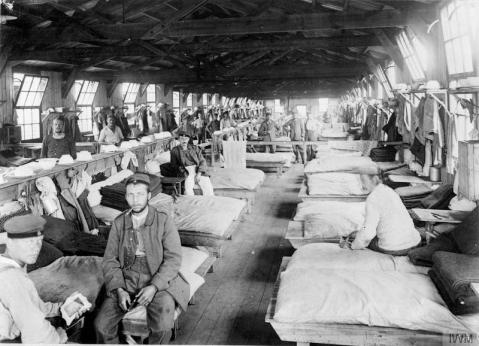

In contrast, significant numbers of military prisoners did not begin arriving in Britain until 1917 (although others had already been interned in France). Although this necessitated the opening of many more internment camps, the British already had a relatively organised system in place for dealing with their prisoners, having already engaged in the wholesale incarceration of the German civilians of military age living in Britain at the outbreak of war.

Image © IWM (Q 64122) – Sleeping quarters for German prisoners at Eastcote Prisoner of War Camp, Northamptonshire (also known as Pattishall).

The conditions endured by prisoners varied widely, depending on who they had been captured by and where. For some men, being held captive was actually more dangerous than serving at the front. Italian and Romanian soldiers seem to have had a particularly bad time of it. British prisoners taken by the Turks suffered similarly. Some men captured on the Western Front were used as forced labour in front line areas, but for many conditions were generally better. The main danger came from illness and disease: during the later war years, several hundred prisoners of war held in Britain died as a result of influenza outbreaks. Typhus was a particular problem in many of the German camps and, after several severe outbreaks, vaccination and hygiene programmes were established to try to control it.

Less obvious, but equally dangerous, were the psychological effects of incarceration. Prisoners had to be active in combating the effects of having little or no privacy, no idea of how long they would be imprisoned for and at best intermittent contact with loved ones back home. Prisoners in many camps did all they could to alleviate boredom and keep their minds occupied, including programmes of education, theatre productions and even camp orchestras.

Image © IWM (Q 23670) – British prisoners of war with a heap of discarded gas masks at a German temporary POW camp on the Western Front.

Conditions in the main camps were monitored by the Red Cross, who also kept extensive records on prisoners’ whereabouts and attempted to establish contact between them and their families. These records have recently been digitised and are available to search at http://grandeguerre.icrc.org/.

While some prisoners attempted to escape (one of the best known escapes was from the Holzminden camp, when 29 British officers escaped through a tunnel they had dug over the course of nine months) the vast majority had to wait for the Armistice before being repatriated. Over 185,000 British soldiers had been captured by that point. Their return home was relatively speedy – the first arrived at Calais on the 15th of November, 1918 on their way back to Dover. The French took longer to bring all their citizens home, partly because there were a great many more of them to deal with. It was the Russian prisoners, though, who had it worse. Many are recorded as still being in Germany as later as 1922.

Grandfather captured on 27th May 1918 12/13th N Fus conditions appalling 2 weeks before his 18th birthday, survived by died by his 35 birthday lied about his age. very good book by Dr Hillary Jones on the conditions of POWs.